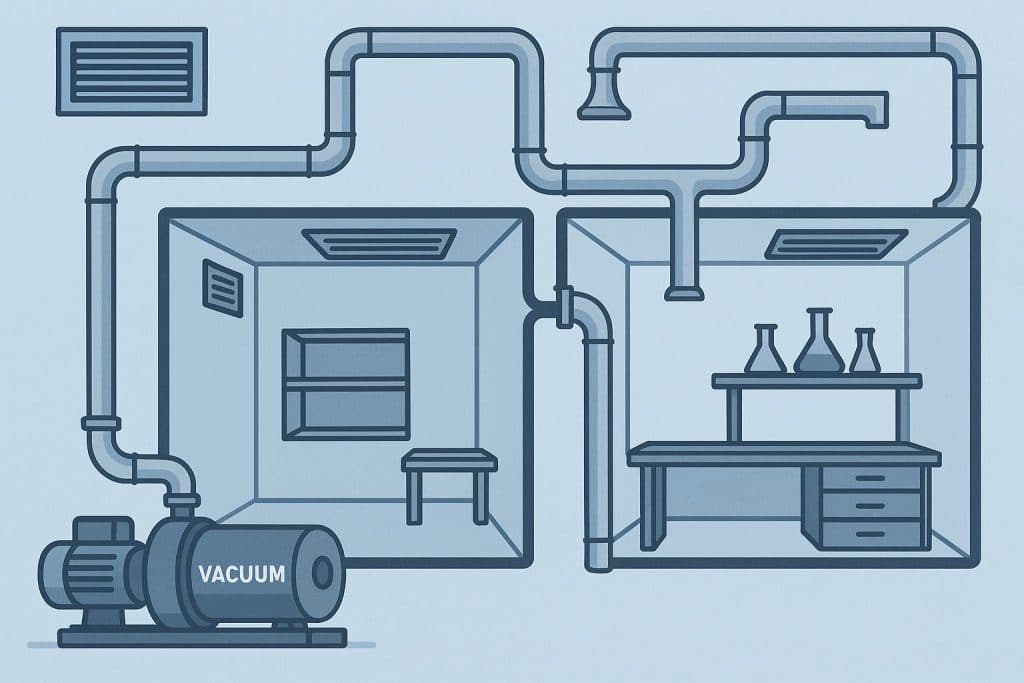

Within the sterile and controlled confines of a modern cleanroom or laboratory, precision is paramount. Every surface is immaculate, the air is filtered to near-perfection, and the work conducted is often at the microscopic scale. Yet, the integrity of this environment depends on a complex and largely invisible world of infrastructure running behind the walls and above the ceilings. This hidden world includes everything from specialty gas conduits to advanced modular piping networks, all designed with a level of precision that mirrors the work being conducted. Among these, the vacuum system is a foundational component, not merely a utility but an active enabler of research and high-tech manufacturing. The principles that govern its design are not just about plumbing; they are about safeguarding the purity of the environment and ensuring the absolute reliability of the processes that lead to innovation and discovery.

The Principle of Purity: Material Selection and Contamination Control

In a controlled environment where a single stray particle can compromise a batch of semiconductors or a sensitive biological sample, the first principle of any infrastructure is that it must not become a source of contamination itself. For vacuum systems, this principle begins with the choice of material. The industry standard is high-grade stainless steel, typically type 316L, chosen for its corrosion resistance and low vapor pressure. But the material alone is not enough. The interior surface of the piping is critical. To prevent the trapping and later release of microscopic particles or molecules—a phenomenon known as outgassing—these pipes undergo a process called electropolishing. This creates an exceptionally smooth, non-porous surface, virtually eliminating potential contamination sites. This uncompromising focus on material purity ensures that the vacuum system removes contaminants from the environment rather than introducing them.

The Principle of Flow: Sizing, Layout, and Conductance

Once purity is assured, the design must focus on performance. The principle of flow dictates that the system must efficiently and consistently remove atmosphere to maintain the required vacuum level at every single point of use. This is governed by a concept called conductance—a measure of how easily gas can travel through a pipe. To maximize conductance, designers must minimize any restrictions. This is why vacuum lines are often significantly larger in diameter than pipes used for pressurized gases. The entire layout of the vacuum piping is therefore a calculated balance, favoring the shortest, straightest paths possible. Where turns are unavoidable, long, sweeping elbows are used instead of sharp 90-degree bends to prevent turbulence that would impede flow. Every element, from the main trunk lines to the final drops at a workstation, is meticulously planned to create an unobstructed pathway for evacuated air.

The Principle of Integrity: Leak-Proof Connections and System Validation

A vacuum system is defined by what it lacks: air. Therefore, its integrity is absolute. A single microscopic leak can compromise the entire network, degrading performance and potentially introducing contamination. This principle of integrity means that traditional threaded pipe connections are completely forbidden, as the threads themselves create a natural leak path. Instead, designers rely on two primary methods for joining sections: orbital welding and specialized mechanical fittings. Orbital welding uses an automated, high-purity process to create a perfectly seamless, permanent joint. For components that may need servicing, high-integrity mechanical connectors that create a metal-to-metal seal are used. Once the system is fully assembled, it undergoes a rigorous validation process, typically a helium leak test, where highly sensitive detectors sniff for any escaping helium atoms to certify a truly hermetically sealed network.

The Principle of Adaptability: Future-Proofing and System Integration

The work conducted in laboratories and cleanrooms is rarely static. New research projects begin, manufacturing processes are updated, and equipment is constantly evolving. The infrastructure supporting this work must therefore be designed with the principle of adaptability in mind. A piping system that is rigid and difficult to modify can hinder innovation and lead to costly renovations. Modern design prioritizes future-proofing, creating systems that can be expanded or reconfigured with minimal disruption to the controlled environment. This need for adaptability applies to all utilities within a modern lab. The design of compressed air lines, for instance, must also account for future equipment additions and changes in demand. By planning these critical systems with connection points for future expansion, facilities can evolve without requiring disruptive and contaminating overhauls.

The Principle of Co-location: Managing Utility Corridors

Vacuum systems rarely exist in isolation. In the dense, technology-rich environment of a lab or cleanroom, they are part of a complex web of utilities that must coexist. The principle of co-location governs the design of the shared spaces—the service chases and interstitial corridors—where these systems run. Here, vacuum lines are routed alongside pipes for specialty gases, process cooling water, and conduits for power and data. The design challenge is to ensure that these systems can operate safely and efficiently without interfering with one another. This requires meticulous planning, including clear and permanent labeling of every line, maintaining specified clearances to prevent thermal or electromagnetic interference, and designing for maintenance access. A well-designed utility corridor ensures that a technician can service one system, such as a water line, without risking the integrity or cleanliness of the adjacent high-purity gas or vacuum networks.

The Unseen Architecture of Precision

The success of a cleanroom or laboratory is ultimately measured by the integrity of the work conducted within it. Behind this success lies an unseen architecture of precision, a network of systems designed and built with the same level of care as the experiments themselves. The principles that shape vacuum piping — purity of materials, efficiency of flow, absolute integrity of connections, adaptability to future needs, and intelligent co-location—are not just engineering guidelines; they are the foundational elements that create an environment of control and reliability. This hidden infrastructure is the silent partner in every discovery and technological breakthrough. Its ultimate achievement is its own invisibility, functioning so flawlessly that it allows scientists and engineers to focus only on the critical work at hand, supported by a perfect, unwavering vacuum.