The Rudnev Case in Argentina — An Investigation by María Vardé

Introduction

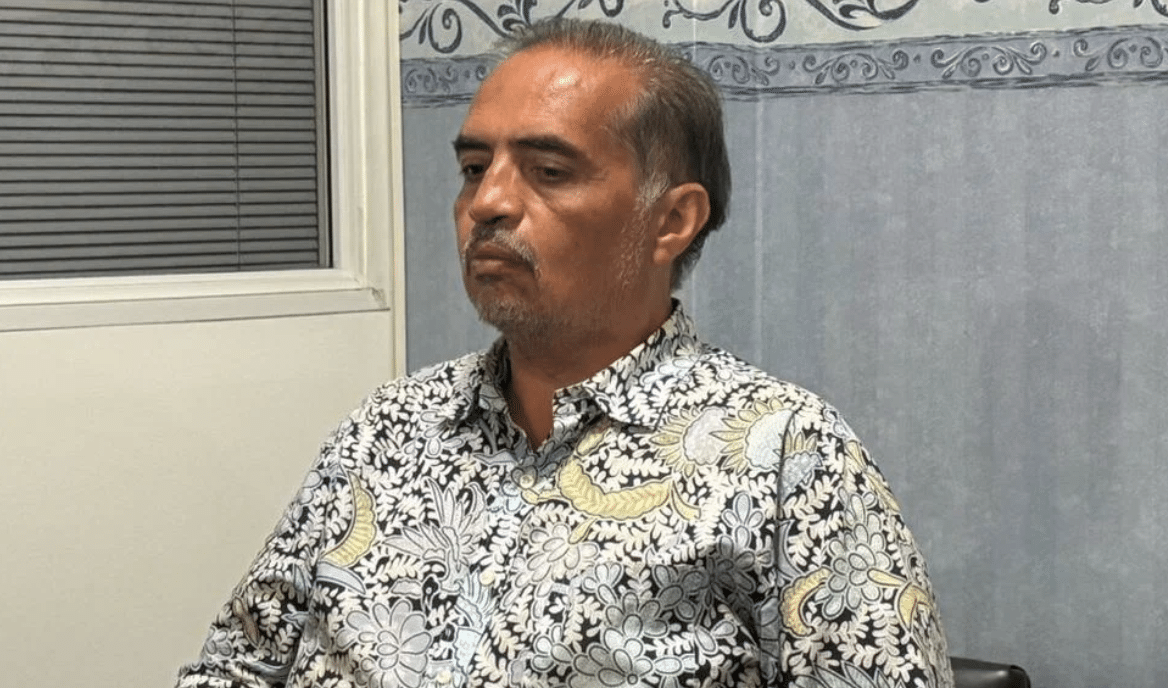

Imagine losing yourself in a maze of suspicion, rumor, and fear — where the walls are cold, the days feel endless, and every hour slowly erodes the body and the mind. This is the reality of Konstantin Rudnev, a Russian citizen who has spent nearly ten months in pretrial detention in Argentina, charged without any material evidence and without a single court conviction — under a vague human-trafficking allegation linked to an alleged “Russian cult.” Fifty kilograms lost. His health is in danger. And yet the only person identified as a “victim” fully denies the accusations.

Detention Without Conviction

No court has established guilt, no trial on the merits has taken place, and no evidence has been proven — yet detention continues. This injustice is not only legal; it is physical, human, and devastating. The Rudnev case is not merely a personal tragedy. It is a window into a system in which pretrial detention too often becomes punishment long before guilt is determined.

A Broader Pattern: Previous Cases

Across Argentina, this pattern repeats itself. In the Buenos Aires Yoga School case, for example, women labeled as “victims” consistently denied any exploitation, while forensic examinations confirmed their capacity to consent. Nevertheless, courts dismissed their testimony as the result of “coercive persuasion.” Elderly defendant Juan Percowicz spent years in facilities deemed unfit for habitation, while Carlos Barragán endured 84 days in detention without essential medication, suffering bone injuries and cardiovascular complications. Media narratives portrayed guilt, while the evidence — or the lack of it — told a very different story.

Recurring Detention Despite Collapsing Accusations

Other cases follow the same chilling rhythm. In the Iglesia Tabernáculo Internacional case and the case of Pastor Tagliabué, defendants spent more than a year — and in some instances nearly three years — behind bars, even as the accusations collapsed under scrutiny. Alleged victims were pressured or misrepresented, and their refusal to accept the label of “victim” was twisted into proof of manipulation. Across these stories, one truth emerges clearly: when moral panic replaces evidence, human lives become collateral damage.

Rudnev’s Current Situation

Rudnev’s ordeal brings this reality into sharp focus. Held in harsh conditions, with his health rapidly deteriorating, he remains imprisoned without a conviction, without proven facts, and without a judicial finding of guilt — in a system that prioritizes fear over facts and optics over justice. A hearing scheduled for January 28 will once again consider the closure of the case, which, according to Rudnev’s lawyer Carlos Broitman, has already been completely dismantled and all accusations have been refuted by the defense. Yet a larger question remains: how many lives are quietly destroyed while the system protects itself?

Institutional Analysis

In her new investigation, María Vardé examines the Rudnev case, the role of PROTEX — Argentina’s federal anti-trafficking office — and frameworks such as “coercive persuasion,” which have repeatedly shaped outcomes in ways that contradict evidence and science. This is not a story about just one man. It is a story about institutions, assumptions, and the dangerous human cost when legal safeguards fail.

Who truly needs whom?

The accused, the so-called victims — or the system itself?