There used to be a ritual associated with using a PC, step by step: go to the computer, sit down, turn on, listen for a whirring sound while waiting through the booting sequence, then start working. This ritual was both sometimes very comforting and sometimes quite annoying. Nowdays however, this ritual seems out of sync with our fast-paced lives.

It seems as though all the devices we have in our day-to-day lives constantly provide us with an “always on” interaction experience. For example, you don’t have to “boot” your phone just like you wouldn’t have to “start” your watch or “wait” for your earbuds before they connect to your device. Instead, these devices are already there and, therefore, waiting and listening in a seamless manner that has changed the way we now expect PCs to interact with us.

Enabling this type of interaction in computing has a name; it is called always-on (and frequently always-connected) computing. Additionally, this term is not merely a marketing tool but instead represents a significant change in what we think of when we think of a “PC” as well as how the PC will utilize various forms of power, networks, and performance.

The emotional truth: waiting feels like failure now

If your laptop takes thirty seconds to wake up from sleep mode, it doesn’t seem very long; it seems like time stopped, and you lost your place in the flow of things due to an interruption. Today’s workday consists of tiny bits of time between longer engagements; responding to a text message in between meetings, pulling a tech document before getting into a cab, reading through notes while cooking dinner, etc. Traditional PCs are built for longer periods of time, whereas always-on devices are built for the real world.

This new approach means that you can open the lid of your laptop, and you will see all your applications, notifications, and the connection to your flow of work is intact when you need them.

Microsoft has been working toward Windows 10 as an extension of that concept for many years, through a technology it calls “modern standby” (S0 Low Power Idle). This enables a smartphone-like “sleep state”, provides for an “instant on/in-and-out of” feature, and allows the ability to keep the laptop connected to the network during sleep.

That single fact of staying connected during sleep is what changes a laptop from being a machine that you need to “power on” to a companion that you have when you want to use it.

Always-on is really about power architecture, not just speed

Traditional personal computers have been constructed and operated with a definite boundary: on or off. When they were asleep (in a classic S3 manner), most of the computer was power cycled off within the unit. This results in a low drain on the device’s battery but leads to slow wake times and a non-living computer experience.

With an always-on computer, that boundary is no longer rigid. The computer has different power states (lightly, intelligently and for those areas that need a break at that precise moment). Modern Standby is the perfect example of this as it provides enough power to the user at a given moment to allow for responsiveness while turning off those components that are not in use.

This same thought process was used to create the magic of a mobile phone, in that you are not concerned about the power state of your phone but how readily available it is. When you have your phone in your possession or when it is off waiting for you to use it.

When that expectation is set then everything else will fall into place; instant wake up will go from being an add-on feature to the norm.

The “connected” part matters more than people admit

When people hear always-on, they picture convenience. But the bigger story is continuity.

A connected PC doesn’t just wake fast. It stays in conversation with your world:

- email and chat updates arrive without you thinking about it

- calendar changes sync quietly

- cloud files stay fresh

- your authentication sessions don’t constantly expire

- Security policies and device management can stay current

The concept of “Always Connected RDPs” that Microsoft introduced was framed within a broader cultural development that is more about their usage than hardware. This cultural shift has resulted in increased mobility, fewer interruptions, and an operating system that behaves much like a phone with respect to how it goes into and out of standby.

Whether you agree or disagree with this idea, it does not change the fact that the workplace has become a distributed population, and connection is taken for granted; the people (or the workplace) in those connections assume that an “always on” computer is like an appliance, whereas an “always connected” computer is modern.

Chips are changing, and they’re dragging the PC with them

As such, the expectation of “always on” has become a reality because computer chips have changed from those that are like a desktop engine inside a portable canister to being designed to always be connected.

Two forces are driving this:

1) Efficiency-first laptop platforms (x86 and beyond)

For example, the Intel® Evo™ program (regardless of what you think of the branding) has established a reasonable expectation for instant wake-up ability and all-day battery life in thin laptops, which provides for “portability” without the need to be “constantly looking for an outlet.”

It is also important to note that the state of always being on is only enjoyable if you don’t have any concern about your battery life. No one wants a laptop that is “always on” by “using up” its battery in a matter of seconds, so it cannot be used as a laptop anymore.

2) ARM-style power behavior is entering Windows PCs

In a similar vein, Qualcomm’s effort towards the development of Snapdragon laptops (and also due to the greater use of Arm architecture for things like smartphones and tablets) is playing a part in pushing PC hardware manufacturers into implementing more phone-level power management into their notebooks. This will be characterised by improved idle efficiency (e.g., more aggressive) when the machine is idle and/or integrating a good number of on-device AI accelerators.

Qualcomm regularly promotes its Snapdragon X series PCs as having “intelligent power management,” which makes them capable of operating for several days, or very long periods of time, between charges. There will be variability in actual battery life from device to device; however, the trend in the industry is around optimising laptops for prolonged periods of time away from an electrical charging source because that drives up our ability to maintain an always-on computing environment that is an enabler of on-device artificial intelligence.

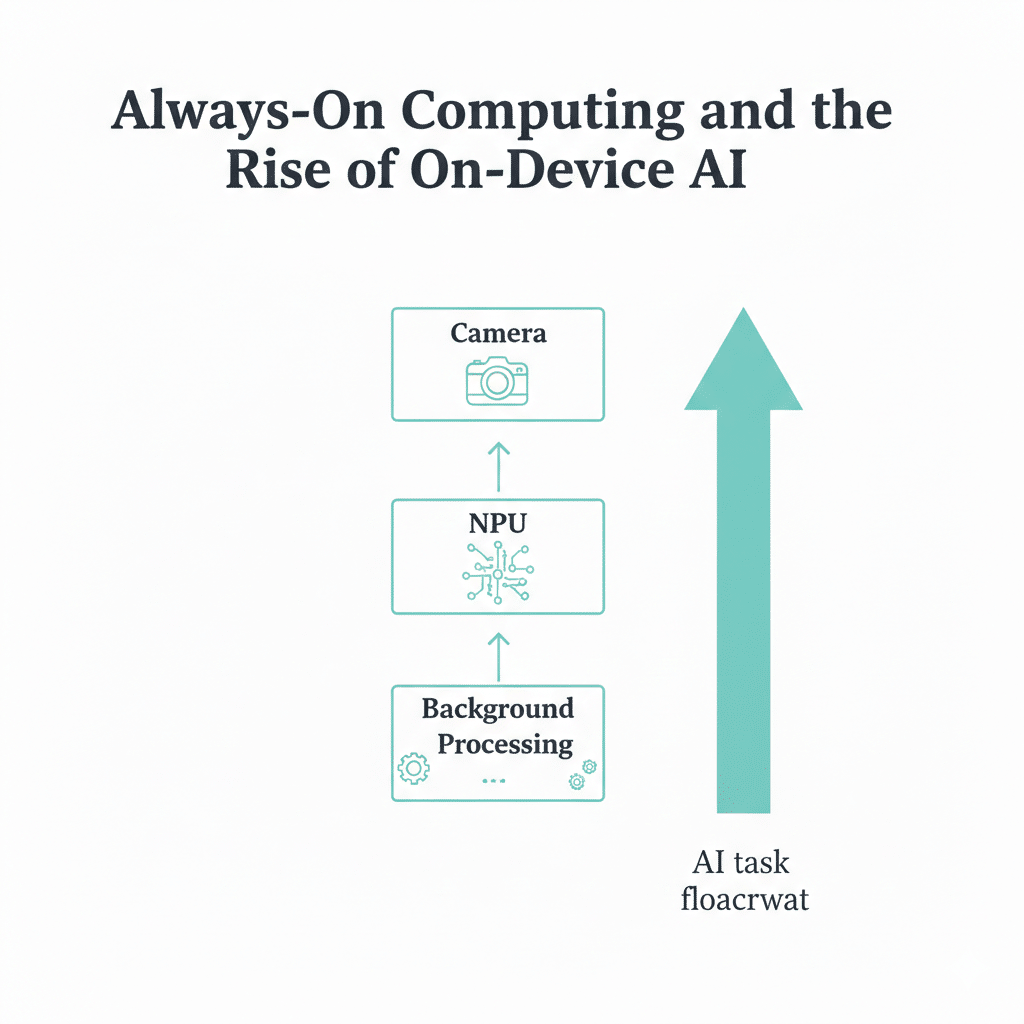

Always-on is also an AI story (quietly)

What essentially people overlook, is that an always-on computing environment will define the way in which we will use on-device artificial intelligence going forward. Essentially what happens in this case is that your notebook computer is designed to be operationally in a constant ‘standby’ mode, which will include things like listening for a wake signal, enabling facial recognition capabilities, handling power states, and processing notifications. In effect, an always-on laptop computer are really no different than the AI-based devices we are in the process of bringing to market.

Today, most laptops include some type of dedicated AI processor (NPU) that provides the capability to perform certain workloads without having to turn on the complete system. Qualcomm has taken a significant stake in this with their commitment to AI processing and low-power consumption through their promotion of the Snapdragon X series platform.

The human impact is subtle but real: your PC becomes less like a tool you operate, and more like a system that anticipates, auto-framing calls, cleaning up audio, summarizing text, surfacing what you likely need next. Some of this is helpful. Some of it is uncanny. But the design logic is the same: stay ready, stay aware, stay efficient.

Why traditional PCs feel like they’re fading

This doesn’t mean desktops are going extinct. If you’re editing 8K video, gaming with a high-end GPU, or running heavy engineering workflows, a traditional PC still makes perfect sense.

But for the majority of people, students, marketers, writers, founders, office teams, computing has shifted:

- Work is cloud-first

- Collaboration is real-time

- Identity is continuous (SSO, passkeys, biometrics)

- Sessions are persistent

- The day is broken into fragments, not blocks

Traditional PCs were optimized for “sit down and do a lot.” Always-on machines are optimized for “drop in, do the thing, move on.”

And that’s why they’re replacing the old default.

The honest downside: always-on can feel too on

If you’ve ever closed your laptop and later found the battery mysteriously drained, you’ve met the dark side of this transition.

Modern Standby has faced criticism from users because it can behave differently depending on drivers, firmware, and device tuning, sometimes waking unexpectedly, sometimes draining more power than people expect from “sleep.” Community discussions often describe S0 as closer to “idle” than true deep sleep, and point out power-consumption concerns versus legacy S3 sleep.

There’s also the emotional tension: a computer that stays connected can feel like a computer that never fully lets you go. Notifications creep. Work can leak into evenings. The device becomes another always-open door.

Always-on computing solves friction, but it can also remove the natural “stop points” we used to get for free.

Where is this heading

Always-on computing is not a feature. It’s a new baseline expectation: instant, persistent, connected, efficient.

It’s the PC learning the manners of modern life.

The lid closes, but your world doesn’t pause. Your work continues syncing. Your messages keep arriving. Your device stays lightly awake, waiting for the next moment you need it.

And once you get used to that feeling, once your laptop starts behaving like it respects your time, traditional PCs begin to feel less like computers, and more like appliances from a slower era.