Introduction:

We live in an era where technology and advanced digital skills have become key drivers of economic growth and geopolitical strength. Tech talent – not oil, not gas – is the new fuel of global power. Nations worldwide are competing through policies and programs designed to attract and retain this talent. This global competition is often referred to as the AI talent race – a contest to secure the brightest minds in artificial intelligence and related fields.

What is particularly interesting is how different countries approach the tech talent race through immigration reform perspective. Some nations are lowering barriers for international professionals – for example, the UK and France with initiatives such as the Global Talent Visa and the French Tech Visa, as they believe that international experience can fill in the skills shortage in critical areas of economy.

While others, like the United States, are gradually limiting immigration opportunities for international talent, arguing that it is more essential to prioritize domestic workers. In this context, the Trump administration announced a new $100,000 payment requirement for H-1B[1] petitions, claiming that the H-1B program has been abused by foreign STEM labor and has contributed to higher unemployment among American workers in computer-related occupations.

To address the critical shortage of skilled professionals, traditional skilled worker visas and their equivalents are no longer sufficient. As a result, countries around the world are increasingly introducing various residence programs to attract exceptional tech talent. For example, China recently launched the K-Visa, effective October 1, 2025. It is aimed at attracting foreign professionals in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, and notably, it does not require a job offer. It is the first significant change in visa regulation in a decade, and it signals that the AI talent race is no longer limited to the U.S., the EU, and the UK – countries in the East are now joining the competition as well.

In this article, we present a case study examining two of the most in-demand visa pathways for tech talent: the UK Global Talent Visa and France’s Passeport Talent[2] covering tech visas. We provide a brief overview of:

- how these visas work and;

- how demand for them has evolved over the years.

- In addition, we examine the factors that influence tech founders’ decisions to relocate to one country or another and explain why the existence of visas alone is not sufficient to build a sustainable AI talent pipeline.

This article analyzes relocation pathways for tech and AI talents in France and the UK, assesses their effectiveness and regional impact, and explains how talent visas have become an essential component of the internal tech ecosystems aimed at competing in the global AI race.

UK vs France – relocation paths:

Attracting world-class talent has been a national priority for both the UK and France for more than five years, explicitly proclaimed at the highest leadership levels – in the UK in 2020 and in France in 2017.

- Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, January 2020: “As we leave the EU, I want to send a message that the UK is open to the most talented minds in the world and stands ready to support them to turn their ideas into reality.”

This statement followed the UK’s exit from the EU. At the same time the cap on the number of talent visas, that had previously existed, was removed.

- Emmanuel Macron, President of France, declared at VivaTech in Paris in 2017: “We want the pioneers, the innovators, the entrepreneurs of the whole world to come to France and work with us on green technologies, food technologies, artificial intelligence, on all the possible innovations. I want France to be the country where new mobility, new energy will be invented and developed. For that, I will ensure that we create the most attractive and creative environment. I will ensure that the State and Government act as a platform and not as a constraint.”

With this statement, President Macron introduced the French Tech Visa – a fast-track four-year renewable residence permit designed to simplify relocation to France for startup founders, tech employees, and international investors.

Since then and up until now, both countries have been actively engaged in developing nationwide tech ecosystems and programs to attract more international talent, while also launching various initiatives to fuel technological development.

Among the key pillars of building leading digital economies are immigration programs for overseas talent.

The UK is globally known for its UK Global Talent Visa and to a lesser extent for Innovator Founder visa. France, in turn, can boast the French Tech Visa under the “Talent Passport” track. Although the names may look similar, they work very differently.

The UK Global Talent Visa (for tech professionals) is overseen by Tech Nation and targets a wide range of professionals with both technical and business backgrounds. The main requirement for applicants is to demonstrate recognized talent. To do this, they must submit a portfolio of supporting evidence, with a maximum of 15 documents. Startup founders, business leaders, engineers, product designers, employees, and freelancers – all can apply for the UK Global Talent Visa, as long as they can demonstrate recognized talent.

The French Tech Visa works differently, offering three main categories:

- French Tech Visa for Founders – for entrepreneurs setting up or scaling an innovative business in France.

- French Tech Visa for Employees – for skilled workers hired by French tech companies recognized as innovative (“jeune entreprise innovante”).

- French Tech Visa for Investors – for international investors making substantial commitments in French tech firms.

Depending on the chosen track, the process of approval (endorsement) for French Tech Visa will look different.

Below are the main comparison factors between the UK and French tech visas: the number of subcategories within the visa, application cost (for 2025), years until citizenship (for 2025), opportunity to bring dependants, volume of required documents, cost of health insurance, the need to demonstrate financial means, and language requirements.

Criteria | UK Global Talent Visa | France Talent Passport |

Relevant Subcategories |

|

|

Application Cost | £561 (Endorsement fee) + £205 (Visa fee) | €99 (Long-stay Visa) + €225 (Residence Permit) |

Path to Citizenship | Eligible after 5–6 years (with ILR) | Eligible after 5 years of residency |

Dependants Allowed | Yes – Spouse/civil partner + children under 18 | Yes – Spouse/civil partner (PACS) + children under 18 |

Document Volume | Up to 15 documents:

| 7–10 documents (varies by subcategory) Generally: passport, proof of qualifications, employment contract or business plan, proof of income/funds, health insurance, proof of accommodation in France, etc.) |

Health Insurance | £1,035/year per person (Immigration Health Surcharge) | Private insurance (€30,000 coverage) before arrival, after receiving your residence permit – access to public healthcare system |

Proof of Financial Means | Not required | Required for most:

€22,000/year (approx.)

€39,582

|

Language Proficiency | No English test required | No French test required |

Both relocation paths are flexible, but in different ways. The UK Global Talent Visa offers broad freedom: holders can work or run a business without sponsorship, employer ties, or language and education requirements. It also provides a transparent pathway to UK citizenship. The way it is designed – combining occupational freedom with a transparent route to a passport – has been a major factor driving demand for this visa Statistics confirm its impact. According to the Global Talent Visa Evaluation: Wave 2 report (March 2024), the existence of this visa influenced at least 80% of applicants in their decision to come to the UK, and over 50% said it influenced their decision to a great extent.

However, when it comes to relocating as a team, the UK Global Talent Visa can be tricky. The visa is strictly individual, so if a startup relocates, each team member must either qualify for it or find another route (such as the Skilled Worker Visa or the Innovator Founder Visa) -– both of which are less flexible than the Global Talent Visa.

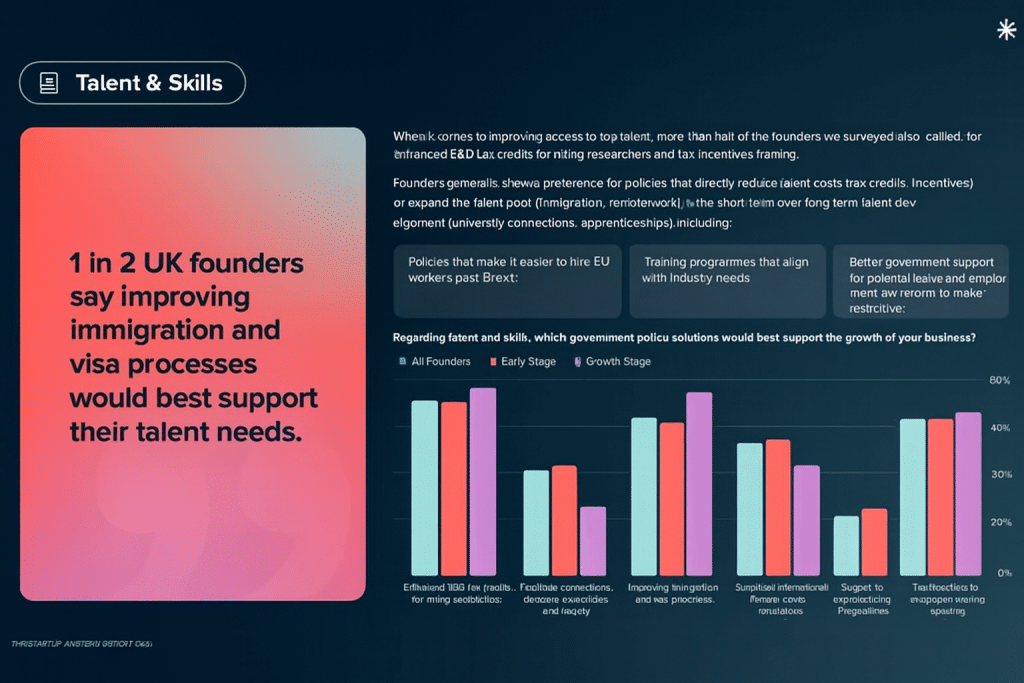

A recent survey indirectly reflects this challenge. According to the Tech Nation Report, “Founders say access to capital, the UK tax environment, and availability of top talent are their biggest barriers to growth.” In particular, founders indicate the availability of top talent as one of the key obstacles, and investors also noted this issue as a factor that affects their willingness to invest according to the report.

It is clear that, despite the existence of the UK Global Talent Visa, the tech sector requires more flexible systems to meet its talent needs.

Source: Tech Nation Report, 2025

In contrast to the UK, France has designed its French Tech Visa system to facilitate not only individual but also team relocations. Under the French Tech Visa for Employees, startups recognized as innovative (“jeune entreprise innovante”) can bring in key specialists alongside the founders, enabling whole teams to move together under one coordinated framework.

This flexibility makes it easier for founders to scale their businesses in France with their core talent on board, rather than facing fragmented immigration routes for each team member. Combined with a renewable four-year permit, automatic family reunification, and no language requirements, France’s approach creates a more holistic environment for international startups seeking to establish themselves in Europe.

In addition, as an EU Member State, France can take advantage of simplified intra-EU mobility rules, which makes transferring employees from other EU countries significantly easier.

Countries in numbers:

Both countries – US and France demonstrate a strong increase in the numbers in people who relocate under the talent visas.

United Kingdom:

According to Dawson, CEO of Founder Group, Tech Nation has supported about 6,400 visa applications since 2014. Earlier statistics indicated that a total of 12,234 endorsements were granted between April 2020 and April 2023 across the six endorsing bodies, with Tech Nation being responsible for 2,931 talent visas :

| Name of the endorsing body | N of visas | % |

| UKRI (UK Research and Innovation) | 3,403 visas | 27.8% |

| the British Academy | 1,208 visas | 9.9% |

| the Royal Society | 1,736 visas | 14.2% |

| Royal Academy of Engineering | 1,175 visas | 9.6% |

| Tech Nation | 2,931 visas | 23.9% |

| Arts & Culture | 1,790 visas | 14.6% |

Source: Global Talent visa evaluation: Wave 2 report

Considering earlier published figures:

- 818 Global Talent Visa endorsements between 2014 and 2018,

- and 4,431 between 2019 and 2023 (or 5,249 in total), with a record 1,620 endorsements granted in 2023 alone[3].

We can conclude that the average number of endorsements has increased dramatically over time: from around 160 per year in the early period (2014–2018) to nearly 700-900 per year in the more recent period (2019–2025) This demonstrates a clear acceleration in demand for the Tech Nation Global Talent route and highlights its growing significance in attracting top international talent to the UK tech sector

France:

Direct figures for French Tech Visa issuance are not publicly disclosed, but broader immigration statistics shows that in 2024 France issued 51,335 economic visas, covering employees, scientists, and entrepreneurs, including French Tech Visa holders. Visas for skilled professionals and scientists increased by 12.5% in 2024, showing France’s push to lead in technological innovation. Visas for self-employed workers and entrepreneurs saw a slight rise (+0.2%). These trends suggest that France is steadily expanding its pool of international talent, with the French Tech Visa positioned as a flagship pathway within this broader strategy.

What else have France and the UK introduced to better equip themselves with AI talent?

However, visas alone are not enough to attract the necessary volume of talent, and the relocation of skilled individuals by itself does not guarantee the desired outcomes. That is why the relocation pathways discussed above have become part of a broader ecosystem aimed at developing the AI and tech sectors. In this context, it is insightful to examine how both countries approach building digital economy–supporting ecosystems.

United Kingdom:

In the UK, for example, Tech Nation – the body responsible for the visa program – also plays a much wider role. It publishes early impact reports on the state of AI in the UK, acting as a think tank and analytical hub. At the same time, it operates as a growth platform, running some of the country’s most important startup incubator programs (Climate, Libra, Future Fifty, Upscale, Rising Stars, Creo). To support newly coming into the UK Talents Tech Nation runs initiatives such as:

- Global Talent Alumni;

- Global Talent Ambassadors;

- Global Talent AI Jobs;

- Global Talent Quantum Job

Economically, Tech Nation’s impact is impressive: over 35% of all UK unicorns have emerged from its programs, generating more than £600 million in gross value added to the UK economy according to their site.

UK example demonstrates how by combining immigration policy with ecosystem-building initiatives like Tech Nation’s programs, the UK has created not only a gateway for global talent but also a launchpad for innovation. Concentrating both visa policy and entrepreneurial support in a single framework has proven to be a smart and innovative strategy – one that other nations competing for AI leadership may need to replicate.

Another example of how the UK is seeking to strengthen its AI talent base is the newly launched Global Talent Taskforce, powered by the £54 million Global Talent Fund. Unlike Tech Nation, which focuses primarily on the business side of technology development, the Global Talent Taskforce is administered by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which also serves as the endorsing body for the scientific route of the UK Global Talent Visa.

The taskforce is designed not only to attract world-class researchers and their teams to the UK but also to cover relocation and research costs for up to five years for selected talent. This program illustrates another example of how the UK is concentrating the supply of AI talent under a single stakeholder with a pivotal role in research, innovation and immigration of talents in spesific field.

France:

France has positioned itself as one of the EU’s most attractive destinations for global tech talent, combining the French Tech Visa with the broader La French Tech brand to signal openness to international founders and professionals. Beyond immigration policy, the country has built a dense innovation ecosystem through coordinated action by ministries, funding bodies like Bpifrance, and flagship programs such as French Tech Next40/120.

This effort is reflected in the numbers. The Global Startup Ecosystem Index (2025) ranks France as the 8th most successful startup nation worldwide, with 30 unicorns. According to Startup Genome, Paris is Europe’s #2 ecosystem in Performance, #3 in Talent & Experience, and a Top 10 global ecosystem in Funding. The city hosts more than 25,000 startups across AI, fintech, biotech, climate tech, and other sectors, together employing over one million people and nurturing a steady pipeline of unicorns. A Reuters (May 2025) analysis shows that between 2017 and 2024, Paris startups multiplied their combined enterprise value by 5.3 times, outperforming London, where growth was 4.2 times.

Anchoring this growth is Station F in Paris, the world’s largest startup incubator, which accommodates around 1,000 startups each year. Since opening in 2017, it has supported over 8,000 companies, including unicorns Hugging Face and Alan (Station F, June 2025). Of its 40 top-performing startups, 34 now place AI at the core of their business (FT, Jan 2025). One of the standouts is Mistral, now valued at €11.7 billion (Le Monde, Sep 2025). Station F–based companies have raised about €1 billion annually for the past three years and reached €800 million in H1 2025 (Station F, June 2025), with programs backed by corporations such as Meta, Microsoft, LVMH, and L’Oréal (Station F, Programs).

At the policy level, the France 2030 plan allocates €30 billion to drive breakthroughs in key sectors from AI to climate tech, with the French Tech 2030 vertical program providing tailored support to 100 high-potential startups in strategically important fields. The French government also backs innovation through one of the world’s most generous R&D tax credits (Crédit Impôt Recherche) and large-scale financing vehicles like the €7 billion Tibi initiative, which channels capital into both early-stage startups and later-stage scale-ups. In February 2025, Macron announced €109 billion in AI-focused infrastructure investments, including new data centers and computing capacity, a project France describes as its equivalent of the U.S. “Stargate” program.

France’s startup ecosystem remains largely Paris-centric, but the government actively promotes regional hubs through 17 French Tech capitals, including Lyon, Lille, Bordeaux, and Marseille – broadening relocation opportunities well beyond the capital. Combined with global outreach events like VivaTech and the Choose France summit, these measures underscore France’s strategy of linking immigration policy with ecosystem development and large-scale investment to cement its position as Europe’s leading startup hub.

Conclusion & Forecasts:

The contest between the UK and France illustrates how immigration policy has become a strategic lever in the global tech economy. Britain’s Global Talent Visa offers unparalleled flexibility for individuals but creates challenges when startups need to relocate as teams. France’s Tech Visa, by contrast, enables collective relocation and reflects the country’s ambition to position itself as the EU’s leading innovation hub.

Neither model is perfect, but together they highlight a clear trend: governments that design visa programs as instruments of industrial strategy – not just border control – gain an edge in attracting the world’s most mobile talent. In the years ahead, Europe’s competitiveness in AI and deep tech may depend less on subsidies or tax breaks, and more on how effectively it welcomes the people building the future.

The question is: what comes next? Although the UK has kept its doors open to international talent and businesses in recent years, its immigration system and approach to building the tech sector have revealed significant vulnerabilities. Mike Bracken, the UK government’s former chief digital and data officer and a founding partner at Public Digital, pointed out: The UK is starting the race for digital sovereignty in the artificial intelligence era from a weakened position – partially because of the years of outsourcing UK data, skills and capacity and high dependance on the international talents in key sectors, including tech. This makes us foresee that the UK will need not only to attract top-tier talent but also to retain it, and it is very likely that this will influence upcoming reforms, including a potential extension of the period required to qualify for a UK passport from five to ten years.

By contrast, in France there has been a trend toward more favorable pathways for Passeport Talent holders seeking naturalization – an approach that can be seen as part of the country’s broader effort to encourage more international talent to settle permanently in France.

At the same time, the EU is preparing a major change for Europe’s immigration landscape. The upcoming reform is the EU Blue Carpet Initiative, part of the Commission’s Startup and Scaleup Strategy (2025–2026). For the first time, startup founders will be explicitly included in EU-level visa and residence rules, placing them on par with highly skilled employees already covered by the EU Blue Card. The Blue Carpet will introduce fast-track residence permits for founders, new frameworks that reward research commercialization, harmonised stock option rules, and simplified recognition of qualifications for EU and non-EU workers. It will also establish “one-stop shop” legal gateways for ICT professionals and simplify rules for remote cross-border work.

In short, the Blue Carpet is the EU’s attempt to “roll out the red carpet” for global tech talent. If implemented effectively, it could reduce fragmentation across member states, strengthen Europe’s ability to retain entrepreneurial talent, and position the EU as a stronger competitor to the U.S. and the U.K. in the global AI and innovation race.

Ultimately, the comparison between different immigration regimes shows that visas are not just about border control – they are about industrial and even geopolitical strategy. France bets on collective relocation and ecosystem branding, while the UK emphasizes flexibility for individuals but faces challenges in retention. The EU, through the Blue Carpet, is attempting to reduce fragmentation and make Europe’s tech ecosystem more competitive. Looking ahead, the economic impact of these programs will extend beyond attracting talent: they will shape where new technologies are built, how innovation ecosystems are financed, and which regions emerge as leaders in the AI era. Investors are more likely to back founders in ecosystems where talent mobility is easier, and that factor increasingly shapes capital flows. As the U.S. tightens and China opens, Europe’s competitiveness in the global AI race will depend on how effectively it balances openness to talent with the depth of its innovation ecosystems.

About authors: We are Beyond Borders ( former name is Ready Visa), a relocation agency for technology professionals. Our work focuses on supporting startup founders, employees of technology companies, and highly skilled digital specialists seeking to relocate to the EU and the UK. This article is our expert opinion on global trends and mobility patterns of tech-sector professionals.

The H-1B visa is a temporary (non-immigrant) visa category in the United States that allows U.S. employers to sponsor highly skilled foreign workers in “specialty occupations.” These roles generally require at least a bachelor’s degree (or equivalent) and involve the practical and theoretical use of specialized knowledge in fields such as technology, engineering, mathematics, and the sciences. Read more.

Since June 16, 2025, the Passeport Talent residence permit has been officially renamed Carte de Séjour Talent under French immigration law. For convenience, we continue to use the term “Passeport Talent” throughout this article.

Tech Nation Global Talent Visa Report: 10 Years of Global Talent in UK Tech, 2024